Domino Theory on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The domino theory is a

geopolitical

Geopolitics (from Greek γῆ ''gê'' "earth, land" and πολιτική ''politikḗ'' "politics") is the study of the effects of Earth's geography (human and physical) on politics and international relations. While geopolitics usually refers to ...

theory which posits that increases or decreases in democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose gov ...

in one country tend to spread to neighboring countries in a domino effect

A domino effect or chain reaction is the cumulative effect generated when a particular event triggers a chain of similar events. This term is best known as a mechanical effect and is used as an analogy to a falling row of dominoes. It typically ...

. It was prominent in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

from the 1950s to the 1980s in the context of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

, suggesting that if one country in a region came under the influence of communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

, then the surrounding countries would follow. It was used by successive United States administrations during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

to justify the need for American intervention around the world. Former U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

described the theory during a news conference on 7 April 1954, when referring to communism in Indochina

Mainland Southeast Asia, also known as the Indochinese Peninsula or Indochina, is the continental portion of Southeast Asia. It lies east of the Indian subcontinent and south of Mainland China and is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the west an ...

as follows:

Moreover, Eisenhower’s deep belief in the domino theory in Asia heightened the "perceived costs for the United States of pursuing multilateralism" because of multifaceted events including the " 1949 victory of the Chinese Communist Party, the June 1950 North Korean invasion, the 1954 Quemoy offshore island crisis, and the conflict in Indochina constituted a broad-based challenge not only for one or two countries, but for the entire Asian continent and Pacific." This connotes a strong magnetic force to give in to communist control, and aligns with the comment by General Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was C ...

that "victory is a strong magnet in the East."

History

During 1945, theSoviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

brought most of the countries of eastern Europe and Central Europe into its influence as part of the post-World War II new settlement, prompting Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

to declare in a speech in 1946 at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri

Fulton is the largest city in and the county seat of Callaway County, Missouri, United States. Located about northeast of Jefferson City and the Missouri River and east of Columbia, the city is part of the Jefferson City, Missouri, Metropolita ...

that:

Following the Iran crisis of 1946

The Iran crisis of 1946, also known as the Azerbaijan Crisis () in the Iranian sources, was one of the first crises of the Cold War, sparked by the refusal of Joseph Stalin's Soviet Union to relinquish occupied Iranian territory, despite repeat ...

, Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

declared what became known as the Truman Doctrine

The Truman Doctrine is an American foreign policy that pledged American "support for democracies against authoritarian threats." The doctrine originated with the primary goal of containing Soviet geopolitical expansion during the Cold War. It was ...

in 1947, promising to contribute financial aid to the Greek government during its Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

and to Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

following World War II, in the hope that this would impede the advancement of Communism into Western Europe. Later that year, diplomat George Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly histo ...

wrote an article in ''Foreign Affairs

''Foreign Affairs'' is an American magazine of international relations and U.S. foreign policy published by the Council on Foreign Relations, a nonprofit, nonpartisan, membership organization and think tank specializing in U.S. foreign policy and ...

'' magazine that became known as the "X Article

The "X Article" is an article, formally titled "The Sources of Soviet Conduct", written by George F. Kennan and published under the pseudonym "X" in the July 1947 issue of ''Foreign Affairs'' magazine. The article widely introduced the term " ...

", which first articulated the policy of containment

Containment was a geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''cordon sanitaire'', which was ...

, arguing that the further spread of Communism to countries outside a "buffer zone

A buffer zone is a neutral zonal area that lies between two or more bodies of land, usually pertaining to countries. Depending on the type of buffer zone, it may serve to separate regions or conjoin them.

Common types of buffer zones are demil ...

" around the USSR, even if it happened via democratic elections, was unacceptable and a threat to U.S. national security. Kennan was also involved, along with others in the Truman administration

Harry S. Truman's tenure as the 33rd president of the United States began on April 12, 1945, upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and ended on January 20, 1953. He had been vice president for only days. A Democrat from Missouri, he ran ...

, in creating the Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

, which also began in 1947, to give aid to the countries of Western Europe (along with Greece and Turkey), in large part with the hope of keeping them from falling under Soviet domination.

In 1949, a Communist-backed government, led by Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC) ...

, was instated in China (officially becoming the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

). The installation of the new government was established after the People's Liberation Army

The People's Liberation Army (PLA) is the principal military force of the People's Republic of China and the armed wing of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The PLA consists of five service branches: the Ground Force, Navy, Air Force, ...

defeated the Nationalist Republican Government of China in the aftermath of the Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on m ...

(1927-1949). Two Chinas

The term "Two Chinas" refers to the geopolitical situation where two political entities exist under the name "China".

Background

In 1912, the Xuantong Emperor abdicated as a result of the Xinhai Revolution, and the Republic of China was est ...

were formed – mainland 'Communist China' (People's Republic of China) and 'Nationalist China' Taiwan (Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

). The takeover by Communists of the world's most populous nation was seen in the West as a great strategic loss, prompting the popular question at the time, "Who lost China?" The United States subsequently ended diplomatic relations with the newly-founded People's Republic of China in response to the communist takeover in 1949.

Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

had also partially fallen under Soviet domination at the end of World War II, split from the south of the 38th parallel where U.S. forces subsequently moved into. By 1948, as a result of the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the U.S., Korea was split into two regions, with separate governments, each claiming to be the legitimate government of Korea, and neither side accepting the border as permanent. In 1950 fighting broke out between Communists and Republicans that soon involved troops from China (on the Communists' side), and the United States and 15 allied countries (on the Republicans' side). Though the Korean conflict

The Korean conflict is an ongoing conflict based on the division of Korea between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) and South Korea (Republic of Korea), both of which claim to be the sole legitimate government of all of Korea ...

has not officially ended, the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

ended in 1953 with an armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the La ...

that left Korea divided into two nations, North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu River, Y ...

and South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and sharing a Korean Demilitarized Zone, land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed ...

. Mao Zedong's decision to take on the U.S. in the Korean War was a direct attempt to confront what the Communist bloc viewed as the strongest anti-Communist power in the world, undertaken at a time when the Chinese Communist regime was still consolidating its own power after winning the Chinese Civil War.

The first figure to propose the domino theory was President Harry S. Truman in the 1940s, where he introduced the theory in order to “justify sending military aid to Greece and Turkey.” However, the domino theory was popularized by President Dwight D. Eisenhower when he applied it to Southeast Asia, especially South Vietnam. Moreover, the domino theory was utilized as one of the key arguments in the “Kennedy and Johnson administrations during the 1960s to justify increasing American military involvement in the Vietnam War.”

In May 1954, the Viet Minh

The Việt Minh (; abbreviated from , chữ Nôm and Hán tự: ; french: Ligue pour l'indépendance du Viêt Nam, ) was a national independence coalition formed at Pác Bó by Hồ Chí Minh on 19 May 1941. Also known as the Việt Minh Fro ...

, a Communist and nationalist army, defeated French troops in the Battle of Dien Bien Phu

The Battle of Dien Bien Phu (french: Bataille de Diên Biên Phu ; vi, Chiến dịch Điện Biên Phủ, ) was a climactic confrontation of the First Indochina War that took place between 13 March and 7 May 1954. It was fought between the Fr ...

and took control of what became North Vietnam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV; vi, Việt Nam Dân chủ Cộng hòa), was a socialist state supported by the Soviet Union (USSR) and the People's Republic of China (PRC) in Southeast Asia that existed f ...

. This caused the French to fully withdraw from the region then known as French Indochina

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China),; vi, Đông Dương thuộc Pháp, , lit. 'East Ocean under French Control; km, ឥណ្ឌូចិនបារាំង, ; th, อินโดจีนฝรั่งเศส, ...

, a process they had begun earlier. The regions were then divided into four independent countries (North Vietnam, South Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam ( vi, Việt Nam Cộng hòa), was a state in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975, the period when the southern portion of Vietnam was a member of the Western Bloc during part of th ...

, Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailand t ...

and Laos

Laos (, ''Lāo'' )), officially the Lao People's Democratic Republic ( Lao: ສາທາລະນະລັດ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ປະຊາຊົນລາວ, French: République démocratique populaire lao), is a socialist ...

) after a deal was brokered at the 1954 Geneva Conference

The Geneva Conference, intended to settle outstanding issues resulting from the Korean War and the First Indochina War, was a conference involving several nations that took place in Geneva, Switzerland, from 26 April to 20 July 1954. The part o ...

to end the First Indochina War

The First Indochina War (generally known as the Indochina War in France, and as the Anti-French Resistance War in Vietnam) began in French Indochina from 19 December 1946 to 20 July 1954 between France and Việt Minh (Democratic Republic of Vi ...

.

This would give them a geographical and economic strategic advantage, and it would make Japan, Taiwan, the Philippines, Australia and New Zealand the front-line defensive states. The loss of regions traditionally within the vital regional trading area of countries like Japan would encourage the front-line countries to compromise politically with communism.

Eisenhower's domino theory of 1954 was a specific description of the situation and conditions within Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

at the time, and he did not suggest a generalized domino theory as others did afterward.

During the summer of 1963, Buddhists protested about the harsh treatment they were receiving under the Diem government of South Vietnam. Such actions of the South Vietnamese government made it difficult for the Kennedy administration

John F. Kennedy's tenure as the 35th president of the United States, began with his inauguration on January 20, 1961, and ended with his assassination on November 22, 1963. A Democrat from Massachusetts, he took office following the 1960 p ...

's strong support for President Diem. President Kennedy was in a tenuous position, trying to contain Communism in Southeast Asia, but on the other hand, supporting an anti-Communist government that was not popular with its domestic citizens and was guilty of acts objectionable to the American public. The Kennedy administration intervened in Vietnam in the early 1960s to, among other reasons, keep the South Vietnamese "domino" from falling. When Kennedy came to power there was concern that the communist-led Pathet Lao

The Pathet Lao ( lo, ປະເທດລາວ, translit=Pa thēt Lāo, translation=Lao Nation), officially the Lao People's Liberation Army, was a communist political movement and organization in Laos, formed in the mid-20th century. The gro ...

in Laos would provide the Viet Cong

,

, war = the Vietnam War

, image = FNL Flag.svg

, caption = The flag of the Viet Cong, adopted in 1960, is a variation on the flag of North Vietnam. Sometimes the lower stripe was green.

, active ...

with bases, and that eventually they could take over Laos.

Arguments in favor of the domino theory

The primary evidence for the domino theory is the spread of communist rule in three Southeast Asian countries in 1975, following the communist takeover of Vietnam: South Vietnam (by the Viet Cong), Laos (by the Pathet Lao), and Cambodia (by theKhmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge (; ; km, ខ្មែរក្រហម, ; ) is the name that was popularly given to members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and by extension to the regime through which the CPK ruled Cambodia between 1975 and 1979. ...

). It can further be argued that before they finished taking Vietnam prior to the 1950s, the communist campaigns did not succeed in Southeast Asia. Note the Malayan Emergency

The Malayan Emergency, also known as the Anti–British National Liberation War was a guerrilla war fought in British Malaya between communist pro-independence fighters of the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA) and the military forces o ...

, the Hukbalahap Rebellion

The Hukbalahap Rebellion was a rebellion staged by former Hukbalahap or ''Hukbo ng Bayan Laban sa Hapon'' (People's Army against the Japanese) soldiers against the Philippine government. It started during the Japanese occupation of the Philippin ...

in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, and the increasing involvement with Communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a so ...

by Sukarno

Sukarno). (; born Koesno Sosrodihardjo, ; 6 June 1901 – 21 June 1970) was an Indonesian statesman, orator, revolutionary, and nationalist who was the first president of Indonesia, serving from 1945 to 1967.

Sukarno was the leader of ...

of Indonesia from the late 1950s until he was deposed in 1967. All of these were unsuccessful Communist attempts to take over Southeast Asian countries which stalled when communist forces were still focused in Vietnam.

Walt Whitman Rostow

Walt Whitman Rostow (October 7, 1916 – February 13, 2003) was an American economist, professor and political theorist who served as National Security Advisor to President of the United States Lyndon B. Johnson from 1966 to 1969.

Rostow worked ...

and the then Prime Minister of Singapore

The prime minister of Singapore is the head of government of the Republic of Singapore. The president appoints the prime minister, a Member of Parliament (MP) who in their opinion, is most likely to command the confidence of the majority of ...

Lee Kuan Yew

Lee Kuan Yew (16 September 1923 – 23 March 2015), born Harry Lee Kuan Yew, often referred to by his initials LKY, was a Singaporean lawyer and statesman who served as Prime Minister of Singapore between 1959 and 1990, and Secretary-General o ...

have argued that the U.S. intervention in Indochina, by giving the nations of ASEAN

ASEAN ( , ), officially the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, is a political and economic union of 10 member states in Southeast Asia, which promotes intergovernmental cooperation and facilitates economic, political, security, militar ...

time to consolidate and engage in economic growth, prevented a wider domino effect. Meeting with President Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

and Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

in 1975, Lee Kuan Yew argued that "there is a tendency in the U.S. Congress not to want to export jobs. But we have to have the jobs if we are to stop Communism. We have done that, moving from simple to more complex skilled labor. If we stop this process, it will do more harm than you can every icrepair with aid. Don't cut off imports from Southeast Asia."

McGeorge Bundy

McGeorge "Mac" Bundy (March 30, 1919 – September 16, 1996) was an American academic who served as the U.S. National Security Advisor to Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson from 1961 through 1966. He was president of the Ford Founda ...

argued that the prospects for a domino effect, though high in the 1950s and early 1960s, were weakened in 1965 when the Indonesian Communist Party was destroyed via death squads in the Indonesian genocide. However, proponents believe that the efforts during the containment (i.e., Domino Theory) period ultimately led to the demise of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War.

Some supporters of the domino theory note the history of communist governments supplying aid to communist revolutionaries in neighboring countries. For instance, China supplied the Viet Minh and later the North Vietnamese army, with troops and supplies, and the Soviet Union supplied them with tanks and heavy weapons. The fact that the Pathet Lao and Khmer Rouge were both originally part of the Vietminh, not to mention Hanoi's support for both in conjunction with the Viet Cong, also give credence to the theory. The Soviet Union also heavily supplied Sukarno with military supplies and advisors from the time of the Guided Democracy in Indonesia

Guided Democracy () was the political system in place in Indonesia from 1959 until the New Order began in 1966. It was the brainchild of President Sukarno, and was an attempt to bring about political stability. Sukarno believed that the parl ...

, especially during and after the 1958 civil war in Sumatra.

Arguments that criticize the domino theory

* In the spring of 1995, former US Secretary of DefenseRobert McNamara

Robert Strange McNamara (; June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American business executive and the eighth United States Secretary of Defense, serving from 1961 to 1968 under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. He remains the Lis ...

said he believed the domino theory was a mistake. Professor Tran Chung Ngoc, an overseas Vietnamese living in the US, said: "The US does not have any plausible reason to intervene in Vietnam, a small, poor, undeveloped country that does not have any ability to do anything that could harm America. Therefore, the US intervention in Vietnam regardless of public opinion and international law is "using power over justice", giving itself the right to intervene anywhere that America wants."

Significance of the domino theory

The domino theory is significant because it underlines the importance of alliances, which may vary from rogue alliances to bilateral alliances. This implies that the domino theory is useful in evaluating a country’s intent and purpose of forging an alliance with others, including a cluster of other countries within a particular region. While the intent and purpose may differ for every country,Victor Cha

Victor D. Cha (born 1960) is an American academic, author and former national foreign policy advisor.

He is a former Director for Asian Affairs in the White House's National Security Council, with responsibility for Japan, North and South Korea, ...

portrays the asymmetrical bilateral alliance between the United States and countries in East Asia as a strategic approach, where the United States is in control and power to either mobilize or stabilize its allies. This is supported by how the United States created asymmetrical bilateral alliances with the Republic of Korea, Republic of China and Japan “not just to contain but also constrain potential ‘rogue alliances’ from engaging in adventurist behavior that might it into larger military contingencies in the region or that could trigger a domino effect, with Asian countries falling to communism.” Since the United States struggled with the challenge of “rogue alliances and the threat of falling dominoes combined to produce a dreaded entrapment scenario for the United States,” the domino theory further underscores the importance of bilateral alliances in international relations. This is evident in how the domino theory provided the United States with a coalition approach, where it “fashioned a series of deep, tight bilateral alliances” with Asian countries including Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan to “control their ability to use force and to foster material and political dependency on the United States.” Hence, this indicates that the domino theory assists in observing the effect of forged alliances as a stepping stone or stumbling block within international relations. This underscores the correlation between domino theory and path dependency, where a retrospective collapse of one country falling to communism may not only have adverse effects to other countries but more importantly, on one’s decision-making scope and competence in overcoming present and future challenges. Therefore, the domino theory is indubitably a significant theory which deals with the close relationship between micro-cause and macro-consequence, where it suggests such macro-consequences may result in long-term repercussions.

Applications to communism outside Southeast Asia

Michael Lind

Michael Lind (born April 23, 1962) is an American writer and academic. He has explained and defended the tradition of American democratic nationalism in a number of books, beginning with '' The Next American Nation'' (1995). He is currently a pro ...

has argued that though the domino theory failed regionally, there was a global wave, as communist or socialist regimes came to power in Benin

Benin ( , ; french: Bénin , ff, Benen), officially the Republic of Benin (french: République du Bénin), and formerly Dahomey, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Togo to the west, Nigeria to the east, Burkina Faso to the north ...

, Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

, Guinea-Bissau

Guinea-Bissau ( ; pt, Guiné-Bissau; ff, italic=no, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫 𞤄𞤭𞤧𞤢𞥄𞤱𞤮, Gine-Bisaawo, script=Adlm; Mandinka: ''Gine-Bisawo''), officially the Republic of Guinea-Bissau ( pt, República da Guiné-Bissau, links=no ) ...

, Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

, Cape Verde

, national_anthem = ()

, official_languages = Portuguese

, national_languages = Cape Verdean Creole

, capital = Praia

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, demonym ...

, Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

, Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

, Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

, Grenada

Grenada ( ; Grenadian Creole French: ) is an island country in the West Indies in the Caribbean Sea at the southern end of the Grenadines island chain. Grenada consists of the island of Grenada itself, two smaller islands, Carriacou and Pe ...

, and Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the cou ...

during the 1970s. The global interpretation of the domino effect relies heavily upon the "prestige" interpretation of the theory, meaning that the success of Communist revolutions in some countries, though it did not provide material support to revolutionary forces in other countries, did contribute morale and rhetorical support.

In this vein, Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara

Ernesto Che Guevara (; 14 June 1928The date of birth recorded on /upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/78/Ernesto_Guevara_Acta_de_Nacimiento.jpg his birth certificatewas 14 June 1928, although one tertiary source, (Julia Constenla, quoted ...

wrote an essay, the "Message to the Tricontinental", in 1967, calling for "two, three ... many Vietnams" across the world. Historian Max Boot

Max Alexandrovich Boot (born September 12, 1969) is an American author, consultant, editorialist, lecturer, and military historian. He worked as a writer and editor for ''Christian Science Monitor'' and then for ''The Wall Street Journal'' in the ...

wrote, "In the late 1970s, America's enemies seized power in countries from Mozambique to Iran to Nicaragua. American hostages were seized aboard the SS ''Mayaguez'' (off Cambodia) and in Tehran. The Soviet Army invaded Afghanistan. There is no obvious connection with the Vietnam War, but there is little doubt that the defeat of a superpower encouraged our enemies to undertake acts of aggression that they might otherwise have shied away from."

In addition, this theory can be further bolstered by the rise in terrorist incidents by left-wing terrorist groups in Western Europe, funded in part by Communist governments, between the 1960s and 1980s. In Italy, this includes the kidnapping and assassination of former Italian Prime Minister Aldo Moro

Aldo Romeo Luigi Moro (; 23 September 1916 – 9 May 1978) was an Italian statesman and a prominent member of the Christian Democracy (DC). He served as prime minister of Italy from December 1963 to June 1968 and then from November 1974 to July ...

, and the kidnapping of former US Brigadier General James L. Dozier

James Lee Dozier (born April 10, 1931) is a retired United States Army officer. In December 1981, he was kidnapped by the Italian Red Brigades Marxist guerilla group. He was rescued by NOCS, an Italian special force, with assistance from the In ...

, by the Red Brigades

The Red Brigades ( it, Brigate Rosse , often abbreviated BR) was a far-left Marxist–Leninist armed organization operating as a terrorist and guerrilla group based in Italy responsible for numerous violent incidents, including the abduction ...

.

In West Germany, this includes the terrorist actions of the Red Army Faction

The Red Army Faction (RAF, ; , ),See the section "Name" also known as the Baader–Meinhof Group or Baader–Meinhof Gang (, , active 1970–1998), was a West German far-left Marxist-Leninist urban guerrilla group founded in 1970.

The ...

. In the far east the Japanese Red Army

The was a militant communist organization active from 1971 to 2001. It was designated a terrorist organization by Japan and the United States. The JRA was founded by Fusako Shigenobu and Tsuyoshi Okudaira in February 1971 and was most active i ...

carried out similar acts. All four, as well as others, worked with various Arab and Palestinian terrorists, which like the red brigades were backed by the Soviet Bloc.

In the 1977 Frost/Nixon interviews, Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

defended the United States' destabilization of the Salvador Allende

Salvador Guillermo Allende Gossens (, , ; 26 June 1908 – 11 September 1973) was a Chilean physician and socialist politician who served as the 28th president of Chile from 3 November 1970 until his death on 11 September 1973. He was the fir ...

regime in Chile on domino theory grounds. Borrowing a metaphor he had heard, he stated that a Communist Chile and Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

would create a "red sandwich" that could entrap Latin America between them. In the 1980s, the domino theory was used again to justify the Reagan administration

Ronald Reagan's tenure as the 40th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1981, and ended on January 20, 1989. Reagan, a Republican from California, took office following a landslide victory over D ...

's interventions in Central America and the Caribbean region

The Caribbean region of Colombia or Caribbean coast region is in the north of Colombia and is mainly composed of 8 departments located contiguous to the Caribbean.Rhodesian Prime Minister

Some foreign policy analysts in the United States have referred to the potential spread of both Islamic theocracy and liberal democracy in the Middle East as two different possibilities for a domino theory. During the

Some foreign policy analysts in the United States have referred to the potential spread of both Islamic theocracy and liberal democracy in the Middle East as two different possibilities for a domino theory. During the

Ian Smith

Ian Douglas Smith (8 April 1919 – 20 November 2007) was a Rhodesian politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia (known as Southern Rhodesia until October 1964 and now known as Zimbabwe) from 1964 to ...

described the successive rise of authoritarian left-wing governments in Sub-Saharan Africa during decolonization

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on separatism, in ...

as "the communists' domino tactic". The establishment of pro-communist governments in Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands and ...

(1961–64) and Zambia

Zambia (), officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central Africa, Central, Southern Africa, Southern and East Africa, although it is typically referred to as being in Southern Africa at its most cent ...

(1964) and explicitly Marxist–Leninist governments in Angola (1975), Mozambique (1975), and eventually Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of S ...

itself (in 1980) are cited by Smith as evidence of "the insidious encroachment of Soviet imperialism down the continent".

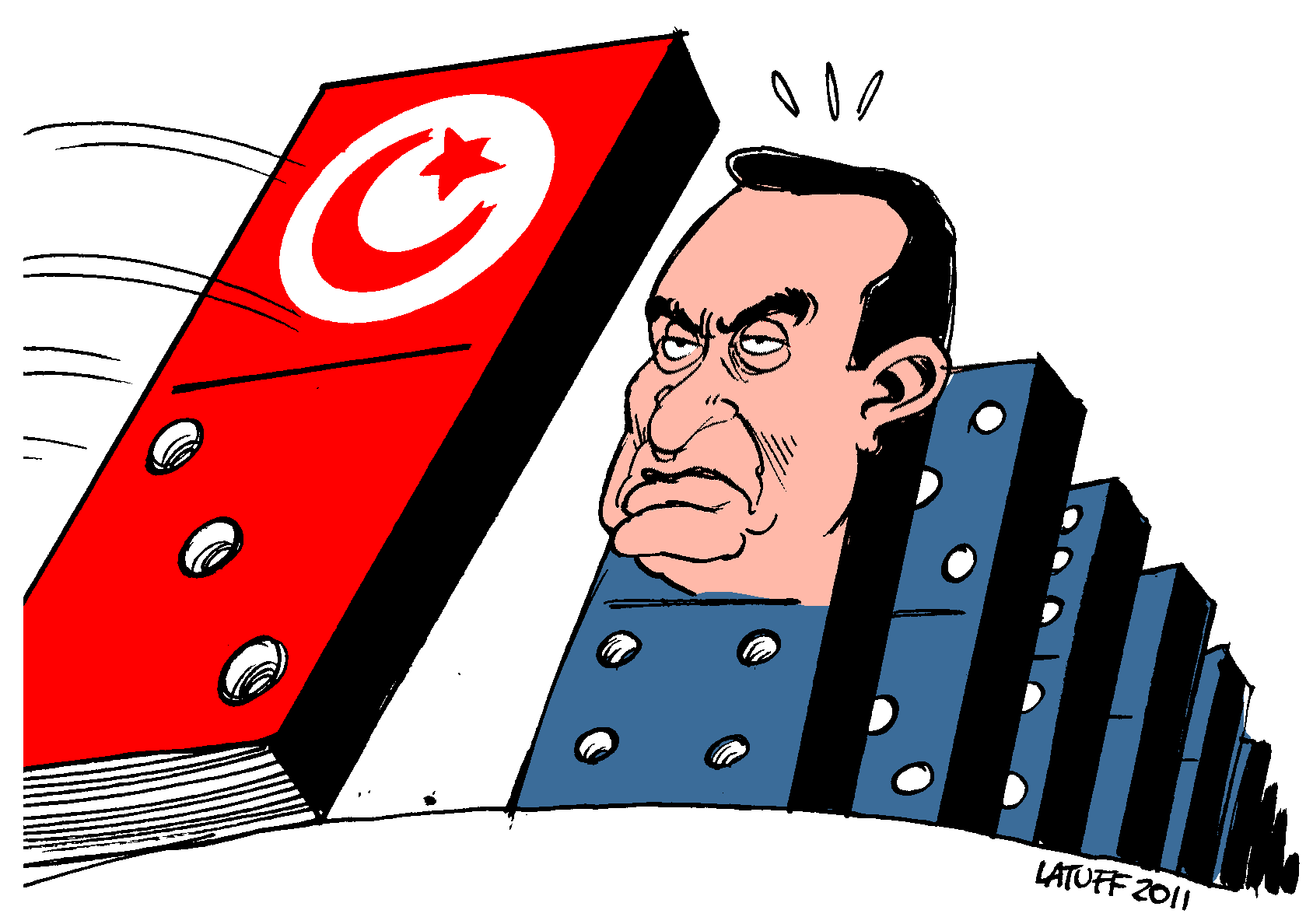

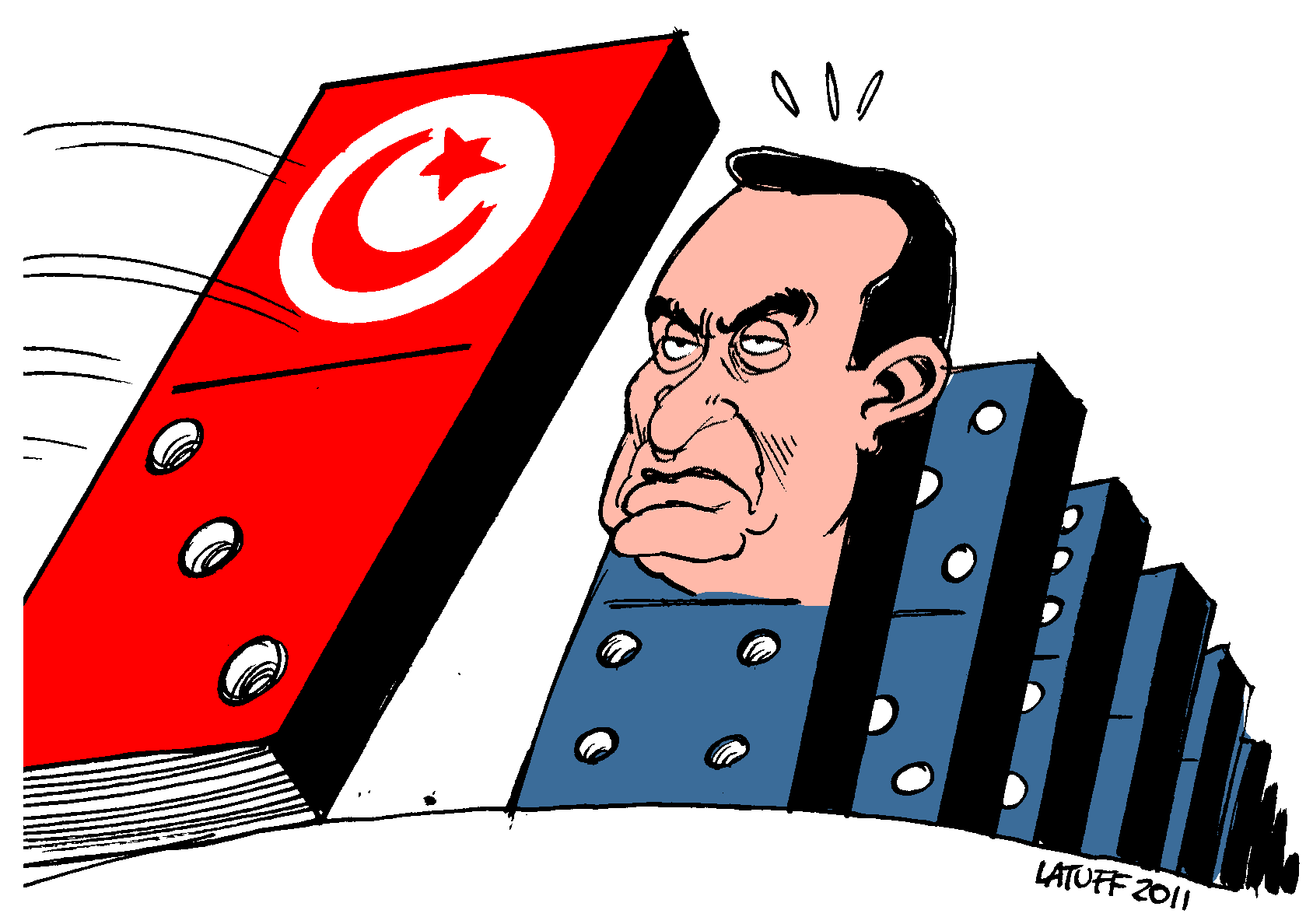

Other applications

Some foreign policy analysts in the United States have referred to the potential spread of both Islamic theocracy and liberal democracy in the Middle East as two different possibilities for a domino theory. During the

Some foreign policy analysts in the United States have referred to the potential spread of both Islamic theocracy and liberal democracy in the Middle East as two different possibilities for a domino theory. During the Iran–Iraq War

The Iran–Iraq War was an armed conflict between Iran and Iraq that lasted from September 1980 to August 1988. It began with the Iraqi invasion of Iran and lasted for almost eight years, until the acceptance of United Nations Security Council ...

the United States and other western nations supported Ba'athist Iraq

Ba'athist Iraq, formally the Iraqi Republic until 6 January 1992 and the Republic of Iraq thereafter, covers the History of Iraq, national history of Iraq between 1968 and 2003 under the rule of the Ba'ath Party (Iraqi-dominated faction), Arab S ...

, fearing the spread of Iran's radical theocracy throughout the region. In the 2003 invasion of Iraq

The 2003 invasion of Iraq was a United States-led invasion of the Republic of Iraq and the first stage of the Iraq War. The invasion phase began on 19 March 2003 (air) and 20 March 2003 (ground) and lasted just over one month, including 26 ...

, some neoconservative

Neoconservatism is a political movement that began in the United States during the 1960s among liberal hawks who became disenchanted with the increasingly pacifist foreign policy of the Democratic Party and with the growing New Left and coun ...

s argued that when a democratic government is implemented, it would then help spread democracy and liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

across the Middle East. This has been referred to as a "reverse domino theory," or a "democratic domino theory," so called because its effects are considered positive, not negative, by Western democratic states.

See also

*Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

* Containment

Containment was a geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''cordon sanitaire'', which was ...

* Export of revolution

Export of the revolution is actions by a victorious revolutionary government of one country to promote similar revolutions in unruled areas or other countries as a manifestation of revolutionary internationalism of certain kind, such as the Marxi ...

* Quagmire theory

The quagmire theory explains the cause of the United States involvement in the Vietnam War. The quagmire theory suggests that American leaders had unintentionally and mistakenly led the country into the Vietnam War. The theory is categorized as an ...

* Red Scare

A Red Scare is the promotion of a widespread fear of a potential rise of communism, anarchism or other leftist ideologies by a society or state. The term is most often used to refer to two periods in the history of the United States which ar ...

* Revolutionary wave

A revolutionary wave or revolutionary decade is one series of revolutions occurring in various locations within a similar time-span. In many cases, past revolutions and revolutionary waves have inspired current ones, or an initial revolution has ...

* Truman Doctrine

The Truman Doctrine is an American foreign policy that pledged American "support for democracies against authoritarian threats." The doctrine originated with the primary goal of containing Soviet geopolitical expansion during the Cold War. It was ...

* World revolution

World revolution is the Marxist concept of overthrowing capitalism in all countries through the conscious revolutionary action of the organized working class. For theorists, these revolutions will not necessarily occur simultaneously, but whe ...

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Domino Theory Cold War terminology Cold War policies History of the foreign relations of the United States Political metaphors Revolution terminology Political theories